This post contains solutions to FiveThirtyEight’s two riddles released 2020-02-07, Riddler Express and Riddler Classic. Code for figures and solutions can be found on my github page.

Riddler Express

The riddle:

From James Anderson comes a palindromic puzzle of calendars:

This past Sunday was Groundhog Day. Also, there was a football game. But to top it all off, the date, 02/02/2020, was palindromic, meaning it reads the same forwards and backwards (if you ignore the slashes).

If we write out dates in the American format of MM/DD/YYYY (i.e., the two digits of the month, followed by the two digits of the day, followed by the four digits of the year), how many more palindromic dates will there be this century?

– Zach Wissner-Gross, “How Many More Palindrome Dates Will You See,” FiveThirtyEight

My approach:

I took a simple brute-force approach. Within a dataframe and using a little code from R’s tidyverse I…

- created a column1 containing each date from now until the end of the century

- created another column that contains the reverse of this

- filtered to only rows where the columns equal the same value

- counted the number of rows

| dates | dates_rev |

|---|---|

| 12022021 | 12022021 |

| 03022030 | 03022030 |

| 04022040 | 04022040 |

| 05022050 | 05022050 |

| 06022060 | 06022060 |

| 07022070 | 07022070 |

| 08022080 | 08022080 |

| 09022090 | 09022090 |

Which shows there will be eight more pallindromic dates in the century – one in each decade remaining.

Riddler Classic

The riddle:

Also on Super Bowl Sunday, math professor Jim Propp made a rather interesting observation:I told my kid (who’d asked about absolute value signs) “They’re just like parentheses so there’s never any ambiguity,” but then I realized that things are more complicated; for instance |-1|-2|-3| could be 5 or -5. Has anyone encountered ambiguities like this in the wild?

— James Propp (@JimPropp) February 3, 2020At first glance, this might look like one of those annoying memes about order of operations that goes viral every few years — but it’s not.

When you write lengthy mathematical expressions using parentheses, it’s always clear which “open” parenthesis corresponds to which “close” parenthesis. For example, in the expression (1+2(3−4)+5), the closing parenthesis after the 4 pairs with the opening parenthesis before the 3, and not with the opening parenthesis before the 1.

But pairings of other mathematical symbols can be more ambiguous. Take the absolute value symbols in Jim’s example, which are vertical bars, regardless of whether they mark the opening or closing of the absolute value. As Jim points out, |−1|−2|−3| has two possible interpretations:

The two left bars are a pair and the two right bars are a pair. In this case, we have 1−2·3 = 1−6 = −5. The two outer bars are a pair and the two inner bars are a pair. In this case, we have |−1·2−3| = |−2−3| = |−5| = 5. Of course, if we gave each pair of bars a different height (as is done in mathematical typesetting), this wouldn’t be an issue. But for the purposes of this problem, assume the bars are indistinguishable.

How many different values can the expression |−1|−2|−3|−4|−5|−6|−7|−8|−9| have?

– Zach Wissner-Gross, “How Many More Palindrome Dates Will You See,” FiveThirtyEight

My approach:

The question is how many ways can you interpret the expression above. As hinted at by the author, the ambiguity in the expression becomes resolved based on where the parentheses are placed. Hence the question is how many different ways can we arrange the parentheses?

Potential parentheses placements

Constraints on placing parentheses:

- Parentheses form pairs, hence there must be an equal numbers of left-closed and right-closed parentheses, i.e.

)and( - We need to avoid adding meaningless parentheses (that don’t lessen ambiguity). Hence like those on the left of this expression should not count as placing a parentheses:

|(-1)|(-2)|(-3)| \(\Leftrightarrow\) |-1|-2|-3|

Hence, we will say…

- A bar can only have a single parentheses placed next to it (either a right or left closed)

- Right-closed will be placed to the left of a bar and left closed to the right of a bar, i.e.

|)and(| - We can ignore the left and right most bars and say that a left-closed parenthese has to go on the left, and a right closed parentheses on the right, hence we can start the problem like “(|-1|-2|-3|)”

With these rules we can tackle the first part of the problem and think of each interior bar as representing a place-holder, the collection of which must be filled by an equal number of ) and ( .

(|−1 _ −2 _ −3 _ −4 _ −5 _ −6 _ −7 _ −8 _−9|)

This can be represented as a combinatorics2 problem that can be represented by \(6 \choose 3\).

We could use the combn() function in R to generate all these combinations.

However, there is a problem; some of the combinations created could result in configurations with open parentheses. For example, even on a shorter version of this problem, the rules above would not safeguard from configurations such as:

that go against the rules of parentheses.

You might take one of these approaches:

- plug all combinations into a calculator and throw-out those that return an error

- define additional rules about the configuration of parentheses that will filter out those configurations, like the one above, that would break (more effort)

I ended-up doing it both ways (was a good way to verify my work). See Define more rules in the Appendix if you want to see how you might take the latter approach. For now, I’ll go the easy route and start computing our expressions.

One thing I needed to do was make it so our mathematical expressions, i.e.:

Could be represented as meaningful expressions within the R programming language, i.e.:

I made an equation create_solve_expr_df() that creates the expressions and computes the solutions. See the raw Rmd file on my github to see my code3.

After creating all possible configurations, I need to actually compute each viable expression to check if any of the configurations resulted in duplicate solutions.

Number of different configurations of parentheses:

solution_9 %>%

nrow()## [1] 70There are 42 individual configurations. However we need to check if all of the evaluated solutions are unique.

solution_9 %>%

distinct(evaluated) %>%

nrow()## [1] 69Given these particular inputs, there are only 39 unique solutions, meaning that three configurations of parentheses led to duplicate solutions.

Appendix

On duplicates

You might wonder if a different set of inputs to the expression \(|x_1|x_2|x_3|...|x_9|\)4 would lead to 39 unique solutions, or if there would be 42 unique solutions – one for each configuration. (I.e. whether the duplicates were specific to the integer inputs -1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7, -8, -9 into the expression, or would have occurred regardless of input).

To verify that you could in fact get 42 unique solutions, I passed in random negative numbers with decimals to see if the function would output unique values for all configurations, or if there would again be duplicates.

set.seed(123)

solution_rand9 <- create_solve_expr_df(-runif(9))

solution_rand9 %>%

nrow()## [1] 70## [1] 70This led to an equal number of expressions and unique solutions – no duplicates. Hence the fact there were duplicates in our problem was specific to the inputs of -1 to -9 not something that would result when inputting any 9 numbers into this expression. I also found this to be the case on longer expressions.

More than 9 numbers

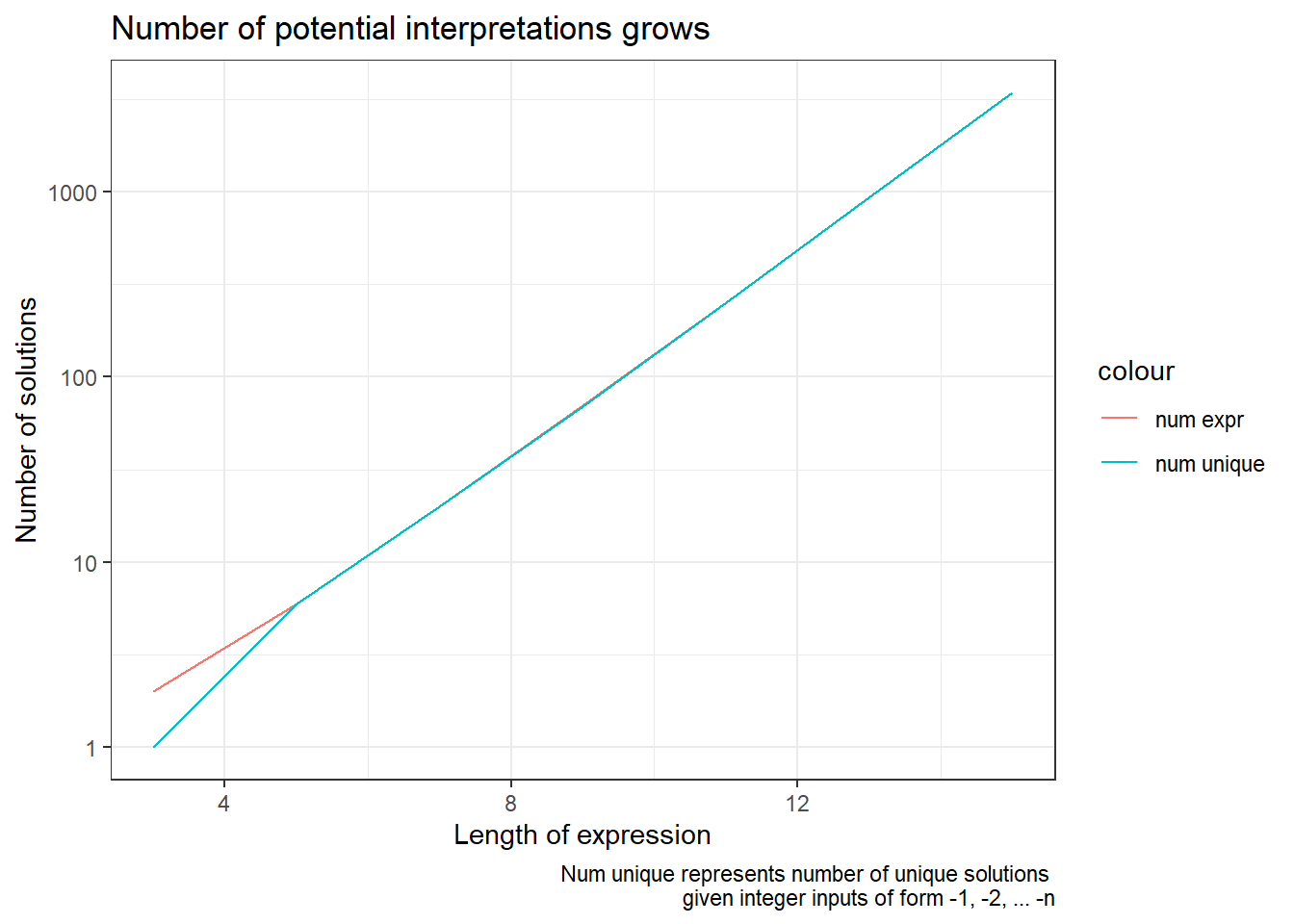

With the above set-up you could calculate the number of configurations for any length of input. Though I found that the computational time required increases quickly (once I started getting into problems into the 20’s things take a long-time to process). See below for a chart of unique solutions from 1 to 155

Define more rules

We could define a few more rules about the configuration of our parentheses.

- Counting from left to right, the number of

)should never exceed the number of( - Counting from right to left, the number of

(should never exceed the number of)

I couldn’t immediately think of a clean way of representing this using combinatorics, so instead decided to run a simulation on our existing subset of combinations from \(6 \choose 3\) that would filter out examples that break the above rules.

My set-up took inspiration from David Robinson’s approach to a different FiveThirtyEight “Riddler” problem.

## # A tibble: 1 x 1

## num_possible_combinations

## <int>

## 1 70- Gives the number of meaningful configurations of parentheses

- Would still need to go and evaluate all of these for the given inputs (-1 to -9)

Creating gif

I used gganimate to create the gif of the different parentheses combinations.

library(gganimate)

set.seed(1234)

p <- solution_9 %>%

mutate(comb_index = row_number()) %>%

sample_n(42) %>%

select(comb_index, equation) %>%

ggplot()+

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-.050, 0.050), ylim = c(-0.1, 0.1))+

geom_text(aes(x = 0, y = 0, label = equation), size = 6)+

ggforce::theme_no_axes()+

theme(legend.position = "none", panel.border = element_blank())

p + transition_states(comb_index)

gganimate::anim_save(here::here("static/post/2020-02-13-fivethirtyeightriddlersolutions-palindrome-debts-and-ambiguous-absolut-value-signs_files/solutions.gif"))vector↩︎

Khan Academy if you want to brush up on your combinatorics skills.↩︎

The code isn’t the most attractive. The dataframe set-up could be cleaner. Also I’d like to go back and rewrite the expression part of this using

rlangand some of the cool things you can do with manipulating environments and expressions in R… but alas… hacked this solution together by just stitching together text…↩︎Note that \(x_n < 0\).↩︎

Note also that this problem requires that there be an odd number of inputs and that they all be negative.↩︎