In this post, I will describe an example of a game that produces many small wins for the player and occasional large wins for the house. Such a game could take advantage of psychological biases of individuals to prefer gains to be disaggregated and losses to be aggregated1 as well as a general disposition for accepting small sure-things when it comes to gains and a willingness to chance higher-risk scenarios in order to avoid paying losses (see Note on Prospect Theory for why these assertions may be inappropriate for the games I describe).

A negated roulette wheel (where the point is to avoid, rather than land on, a specific number) provides a simple example of a game that captures these dynamics2.

All types of games described in this post would need to be empirically evaluated in a gambling / gaming environment. The ideas are very much in a draft form3. The games discussed align with some psychological biases while potentially running counter to others4 – reading more on prospect theory and related ideas is required to more carefully consider approaches in game design5. See Note on Prospect Theory in the Appendix for a retrospective discussion on errors I make in this post in applying psychological biases to gambling.

Biases in Value

On Wednesday’s I co-lead an internal study group on Pricing Strategy. We just finished week four of Customer Value in Pricing Strategy. The material in this section is devoted almost entirely to the various conditions under which people behave ‘irrationally’6 and how / when a firm can manipulate the psychology of customers to demand a higher price for their products. The subject matter is rife with ethical dilemmas; setting these aside, the material sparked an idea for a new spin on games and gambling.

There are a few psychological phenomena from the course that are important primers.

I. People tend to be risk seeking when facing losses but risk averse when facing gains.

An example in the course is that, faced with the scenario below, people will tend to go for the sure thing and win $50 rather than the chance at gaining $100 (even though each option has the same expected value).

(all images in this section are screenshotted from the coursera materials created by the University of Virginia and Boston Consulting Group)

Though when facing potential losses, people prefer taking their chances and will tend to select the option with the risk of a greater loss (for the possibility of avoiding the loss entirely). They will choose a 50% chance of losing $100 (to avoid a guaranteed loss of $50).

- People tend to prefer disaggregated gains but aggregated losses

People prefer multiple small good events over a single (larger) good event (even if the total value is equal). For example, people will prefer winning two low value scratch cards over winning a single higher value scratch card:

However people prefer taking losses in aggregated forms. As described in the course, they usually prefer receiving one large bill over multiple smaller bills:

Even though, as with the previous examples, the value of the events are equal7.

Implications for Gambling

Many lotteries, slots, and other forms of gambling run counter to these particular psychological phenomena8. They offer repeated guaranteed initial losses (the quarter you put into the machine, the scratch ticket you buy from the counter, etc.) for the chance at a large payoff (winning the jackpot).

I thought an interesting set-up for a game would be one that flipped this and made the player very likely to win a small amount each time they played but that always carried the risk of a single large loss9.

As an example, imagine a roulette-like wheel numbered from 1 to 10. You are instructed to pick a number. As long as you don’t land on that number you will win $5. If you do land on it you will lose $50 (or something along those lines for whatever size of bet10). This particular bet would yield the casino an expected value of 50 cents11. It also yields the player the excitement of an expected nine wins in a row12. The advert for the game might focus on the idea of “Tempting Fate13.”

You could blend these ideas with other common gaming features. For example, you might have a mix of ‘big losses’ and ‘big wins’. Carrying on from the previous example, the wheel (numbered 1:10) could be set-up where the player selects a number for a ‘big win’ ($50 gain), and two ‘big losers’ ($50 loss for either), and the rest resulting in small wins ($5). The expected value for the casino on this set-up is now $1.5014.

There are a variety of forms this game could be tested in – it doesn’t have to be a roulette-like wheel in a casino (I actually think an app or more gamefied environment may work better15). The novel feature is ensuring players get repeated high-likelihood small wins while having them pay their losses in one-off large losses (rather than small incremental payments).

Appendix

Note on Prospect Theory

Section added after writing post and after reading a little more on Prospect Theory.

The course materials I reference in this post are themselves referencing research on when a player is facing either only gains (guaranteed gain vs possible gain) or only losses (guaranteed loss vs possible loss). However in gambling the problem is mixed. Players face both the possibility of gains or losses on any given bet. Khaneman describes the differences in the mixed case in Chapter 26, Prospect Theory of his book Thinking Fast and Slow:

“In mixed gambles, where both a gain and a loss are possible, loss aversion causes extremely risk averse choices. In bad choices, where a sure loss is compared to a larger loss that is merely probable, diminishing sensitivity causes risk seeking. There is no contradiction. In the mixed case the possible loss looms twice as large as the possible gain.”

This suggests that my assertions throughout later parts of this post regarding risk seeking behaviors are likely incorrect16. This misapplication however might not present as much of a problem for my references of people’s preference for aggregated losses and disaggregated gains. Hence at least part of my justification for hypothesizing a game like “Wallet Roulette” may be applicable17.

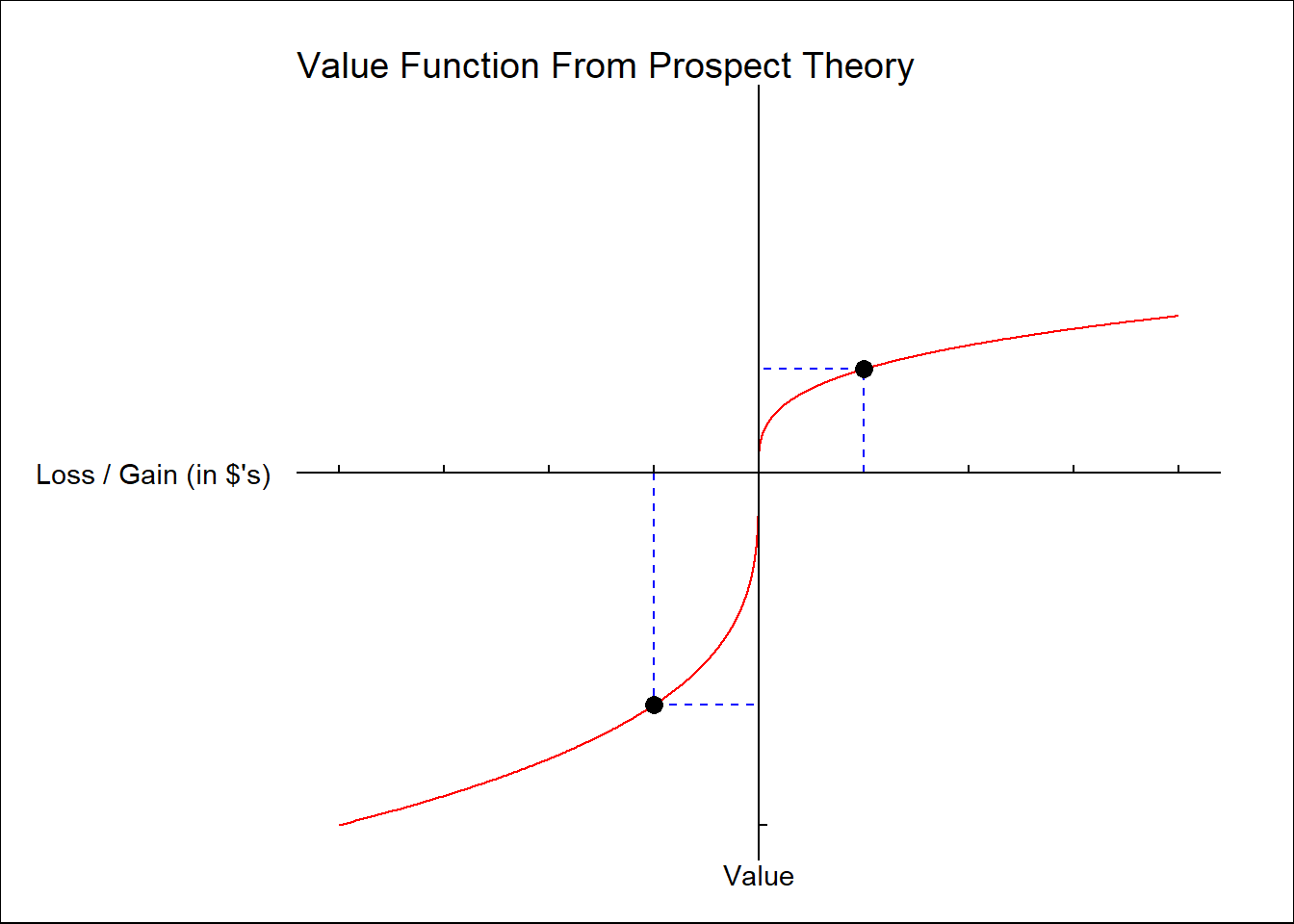

It remains possible that multiple gains may represent greater value than a single larger loss. The chart below shows a typical example of the asymmetric S-shaped value function associated with gains/losses in Prospect Theory. Even with its asymmetry (whereby losses are felt more intensely than gains) it is clear that three gains (i.e. wins) of $0.05 would more than offset a single loss of $0.15 (assuming the value derived from individual gains can be aggregated linearly). Hence the types of games I describe may still be worth exploring in gambling contexts.

(Note that a previous version of this post had linked to a figure from Wikipedia. The current version was created using the ptvalue() function for the “Prospect Theory Value Function” from the econocharts package in R.18)

One explanation for why people gamble at all is people’s tendency to overweight the likelihood of rare events19. While this explains participation in lotteries and sweepstakes it does not explain all forms of gambling. These other forms of gambling present additional challenges for Prospect Theory20 to explain. Nick Barberis explains why a Prospect Theory agent may choose to gamble in A Model of Casino Gambling, where he writes:

“What is the intuition for why, in spite of loss aversion, a prospect theory agent might still be willing to enter a casino?… We show that, if the agent enters the casino, his preferred plan is to gamble as long as possible if he is winning, but to stop gambling and leave the casino if he starts accumulating losses.”

The games I describe may appeal to this particular type of agent in that the games would be designed for the player to accumulate wins.

The paper describes gamblers with different starting profiles. Variety in motivations and behaviors of gamblers opens the possibility that the types of games discussed in this blog post may appeal to a certain set of players (particularly those that are motivated by the feeling of winning rather than an overweighting of the tails of the probability distribution that likely motivates participation in lotteries and sweepstakes21). I would also suggest that there is ample room to improve the value players derive from slot machine like games22 by applying ideas from Prospect Theory and other research into human behavior23.

Wallet Roulette

Below I will describe the rules for a game that I’ve come-up with called “Wallet Roulette24” that is designed to take advantage of the ideas described in the post above25. The game is set-up to look and feel somewhat similar to a slot machine but with a win / loss structure that is almost the complement of that in slots26.

The virtual game is set in a dingy bar-like setting with shady (though cartoonish) figures holding wads of cash in their hands and crowded at the edges of the screen. They stare at you expectantly. A sinister looking attendant standing behind the bar administers play.

The game begins when you take a wallet, fill it with money (your bet) and place it in front of you. A gun, a revolver, with six chambers in it is pointed at your wallet. The round starts when you fill one of the chambers with a bullet, spin the cylinder, wait for it to come to a rest, and pull the trigger. If the gun fires, your wallet explodes and the money flies out and is scooped up by the shady figures. If it clicks (having landed on an empty chamber) the attendant grimaces and slides some money to you from across the counter27. You then decide whether to play another round (filling a new wallet with money if your previous one had exploded) or you take out your money and leave.

For a six-shooter, a $30 wallet would need to payout less than $6 for the house to have an advantage. An expected value for the user of \(\frac{5}{6}\) to \(\frac{11}{12}\) on the dollar could be appropriate (~83.3 to ~91.7 cents for every dollar gambled)28. Hence for a wallet filled with $30 there would be a payout of between $5 and $5.50 for a miss.

Game Options:

The game options below are some top-of-mind notes regarding features, options, and gameplay for “Wallet Roulette.” This is neither a necessary nor exhaustive list29.

When describing payout rates for particular game configurations, I stick with an ~83.3 to ~91.7 cent return on every dollar gambled for the player (so will usually report what the event would look like at each of these payout rates).

- You may be able to add multiple bullets to the chambers, which will increase payouts (along with the risk the player is taking on).

- For example, for the $30 wallet and a six shooter, adding a second bullet would change the payouts on a miss to be between $12.50 and $13.75 (using the previously described payout rates)

- There are reasons not to allow for half or greater of the chambers to be filled30, but say this is allowed, the other payout rates on a $30 wallet with a six-shooter would be:

- 1 bullet: $5 to $5.50

- 2 bullets: $12.50 to $13.75

- 3 bullets: $25 to $27.50

- 4 bullets: $50 to $55

- 5 bullets: $125 to $137.50

- Players can also have the option of adding “money bullets” to the chamber. These bullets (if triggered / landed upon) infuse the wallet with additional cash (they shoot money into the wallet). The catch is that when adding a “money bullet” to the chamber, perhaps the player must also add a regular bullet.

- By default triggering a “money bullet” would double the size of the wallet.

- This default behavior though represents a bad deal for the player. Two regular bullets and one “money bullet” in a six-shooter reduces the expected win rate for the player to 75 to 77.5 cents on the dollar (if the ‘miss’ payout rates are unchanged).

- If we wanted to keep the dollar win rate the same when adding a “money bullet” the bullet would need to be worth more like \(\frac{7}{6}\) the value of the wallet (i.e. ~$35 rather than $30 in this case) alternatively the value of ‘misses’ could be increased31.

- The bullet in the cylinder can either be shown or obscured (while it is spinning). Being able to see it makes the gameplay feel almost identical to roulette32. I slightly prefer the idea of not being able to see the bullet in the chamber, that way you only know the outcome once the trigger is pulled.

- Playing with the bullet’s position obscured would allow for the player to add or take money away from the wallet up until right before pulling the trigger (adding suspense and potentially some last second hand-wringing).

- Keeping the bullet’s position obscured also provides the option to pull the trigger multiple times during a round. The payout rate would go up for each time you pulled the trigger in a round.

- It may make sense to have a limitation on the number of times in a round that the trigger can be pulled33. If you do allow multiple trigger pulls, the items below show what the payout would be for each pull within a round34:

- 1st trigger pull: $5 to $5.50

- 2nd pull: $6.25 to $6.80

- 3rd pull: $8.33 to $9.17

- 4th pull: $12.50 to $13.75

- 5th pull: $25 to $27.50

- It may make sense to have a limitation on the number of times in a round that the trigger can be pulled33. If you do allow multiple trigger pulls, the items below show what the payout would be for each pull within a round34:

- As the player plays more they can update their gear for the game. For example they may be able to get…

- a fancier cylinder, handle, trigger, or other part of the gun or a different gun entirely

- different types of bullets with different types of animations that go with them

- a nicer wallet

- decals on your gear

- Most of these player earned items wouldn’t change game outcomes but would simply provide different animations or game stylings.

- however they may be able to earn things like “super money bullets” or other accelerators with better payouts than described in the default behavior (but not erasing the house advantage)35).

- I am debating whether payouts to the player should default to be payed directly to the player or to be added to their wallet. I lean towards having the payouts default to be given directly to the player36.

- If the game is played in a casino, the dollars in the player’s account could be tied to a player card or account with the casino (which they use to fill their wallet for the game). If playing through an application or online it would be tied to their login. The same goes for any gear or other items they’ve earned as a part of playing37.

- It may make sense to allow play with cylinders with different numbers of chambers in them, e.g. sizes of 5, 6, 10. Cylinders with more spots will generally have smaller payouts. My guess is 5 to 9 chambers would be the sweet-spot. People tend to overestimate the likelihood of very rare events, so a cylinder size of 20, 50, etc. would probably be too large38 (as the smallness of payouts would not be commensurate with the perceived risk the player is taking on).

- At the start, the player may be able to choose between two types of guns: a standard revolver, or a nerf gun equivalent. Both would play the same39. The nerf gun option is just a way of providing an option for players with a distaste for guns.

- For cases where the game is played at a physical casino (rather than through an application), there could be a crank bar or wheel that when interacted with initiates the spinning of the cylinder. Once the cylinder stops spinning, there could also be a physical trigger that a player pulls in order to play the round40.

- One limitation with the game is that it doesn’t, as described, have the potential allure of a ‘jackpot’ which can be a highly motivating factor. Maybe there can be some imperceptible chance set that the bullet would hit a coin inside the wallet, deflect off, and hit the cashier where the attendant keeps the money, exploding that and thereby sending it to you (or some other contrivance to allow for the possibility of a jackpot).

Picture the pattern of gains and losses in the stock market – where rises are typically more incremental compared to the steepness of drops.↩︎

Credit card roulette (whereby friends throw in their cards at the end of dinner to see who will end-up paying for it) perhaps provides an everyday example for the type of game I’m talking about.↩︎

There is a decent chance I misapplied some concepts – particularly regarding the idea of risk seeking when it comes to losses (e.g. if it’s more about seeking uncertainty vs seeking riskiness…). What I describe also seems to run counter to the idea that sporadic positive events help drive repeat behaviors whereas sporadic negative shocks drive avoidance of the activity. Generally I would need to think about and read a little more…↩︎

A potential issue with my examples is with the ‘framing effect’ – I largely frame things in terms of ‘losses’ (particularly in the Wallet Roulette game which may actually push players towards more risk-averse behavior. For example people’s tendency to underweight rare events and a closer consideration of the importance of reference points are just a few ideas that require closer consideration.↩︎

As doing so goes against some of the psychological principles of the game (of keeping win-rates high) and risks making the payout rates for the player to be too explicit (when there is an equal likelihood of winning and losing it becomes obvious what the payout rate is… it may be to the houses advantage to keep this obscured). On the other hand, allowing this may be helpful in that it allows the player to set their risk threshold. On the whole I probably lean towards allowing the players to fill the gun with their wallets as it empowers them to pick their own risk level.↩︎

I am also in the middle of reading Khaneman’s highly related seminal book “Thinking Fast and Slow”.↩︎

Ignore the particularities in the examples and focus on what they are designed to illustrate…↩︎

However they play at others. Casinos are master psychological manipulators. I imagine they have thoroughly tested the ideas discussed in this post.↩︎

Picture a group of friends playing credit card roulette at the end of the night.↩︎

one can of course edit the odds to set things appropriately↩︎

I imagine casinos have considered setting games like this up and that there are good reasons they don’t exist. For example, players have to put up a lot of money to win anything, so the dollars that go to the house per dollar bet is going to be much lower than other games that they could fill their floor space with. At least for the examples I go through in this post… I actually think a bit less of an imbalance would be better, as suggested by Wallet Roulette as described in the Appendix.↩︎

Many casino games could be redesigned in this manner – where you are likely to win but always face the risk of a large loss. You might picture a room in the casino that had an ‘Upside Down’ style feel where all the slots and similar games there were reconstructed accordingly.

It also could make sense to have bets be placed across the number – this resemble a ‘place bet’ being made across multiple numbers in craps (where the player is crossing their fingers hoping against a seven being rolled).↩︎

As an example imagine a facsimile of a game where you search fantastical caves for treasure – you usually find small bits, but occasionally stumble upon a pack of dwarves that rob you. If the game points are translatable into money this represents the same thing. An app environment also helps to divorce the user from the sting of the extreme losses (that come from the design of this type of game).↩︎

As the psychological biases I describe do not apply to mixed environments where a player can achieve either a gain or a loss.↩︎

Though it may also be that the fear or a ‘ruining’ loss would discourage play.↩︎

Of which I helped contribute to the development.↩︎

I.e. they think they have a better chance of winning that they do.↩︎

As well as other behavioral economic theories↩︎

This is also a more optimistic outlook on the value players stand to derive from gambling.↩︎

Which I typically find quite boring currently.↩︎

Including those principles I might have missed.↩︎

or "Russian Wallet Roulette" or some variation on this.↩︎

The game though does not reflect a complete embodiment of Prospect Theory applied to gambling. See footnotes from beginning of post for notes on this as well as the section Note on Prospect Theory. Obviously though this game is framed as a loss, which may run counter to the type of game that a Prospect Theory agent may want to play.↩︎

I.e. the player typically has small wins followed by occasional large losses whereas slots tend to have small losses with occasionally larger wins (slots also feature small payouts, so this is speaking generally). In the “Game Options” I provide ways by which a player could set their own risk profile (e.g. by filling their gun with more bullets, changing the cylinder size, etc.). Hence I also envision the game having a bit more customizability compared to what is typical in slots.↩︎

This gets added to your account or can be added to the wallet, i.e. your bet.↩︎

Slot machines typically hover around a 10 cent on the dollar advantage for the house.↩︎

Some of these ideas enhance or modify play more than others. Many of these would need to be tested on players to determine the ideal options to set for the game.↩︎

As doing so goes against some of the psychological principles of the game (of keeping win-rates high) and risks making the payout rates for the player to be too explicit (when there is an equal likelihood of winning and losing it becomes obvious what the payout rate is… it may be to the houses advantage to keep this obscured). On the other hand, allowing this may be helpful in that it allows the player to set their risk threshold. On the whole I probably lean towards allowing the players to fill the gun with their wallets as it empowers them to pick their own risk level.↩︎

Though this approach seems less appealing.↩︎

An advantage with this is that it may reassure the player by making it appear more fair – as they can see the bullet moving↩︎

As doing so goes against some of the psychological principles of the game (of keeping win-rates high) and risks making the payout rates for the player to be too explicit (when there is an equal likelihood of winning and losing it becomes obvious what the payout rate is… it may be to the houses advantage to keep this obscured). On the other hand, allowing this may be helpful in that it allows the player to set their risk threshold. On the whole I probably lean towards allowing the players to fill the gun with their wallets as it empowers them to pick their own risk level.↩︎

If keeping to previously described payout rates for a six shooter with one bullet in it.↩︎

These “super money bullets” may keep the win-rate near \(\frac{5}{6}\) rather than making it worse – as described in the bullet on default “money bullet” behavior above. Using Prospect Theory lingo, the default “money bullet” option becomes a “dominated” option.↩︎

The potential advantage of putting them in the wallet is that it increases their bet size. The downside is that if they lose the wallet, the player may be left feeling like they haven’t won anything. Hence leaning towards having the payout go to the players account directly.↩︎

So they keep items they’ve earned even if they return to play later.↩︎

The animation may also look awkward, as it would be a revolver with a tremendous number of bullets… a tommy gun would almost be more appropriate.↩︎

but may have slightly different animations when fired↩︎

For a phone or computer application, these parts of the game would be interacted with via touch screen or mouse.↩︎